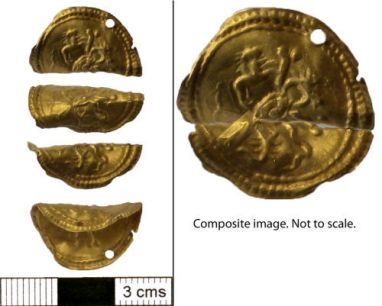

Perhaps one of the most incontrovertibly ‘magical’ objects from Roman Britain is a gold disc depicting a scene in which the Evil Eye (the supernatural personification of ‘bad luck’) is suppressed by its enemies. It was recorded by the Portable Antiquities Scheme (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Gold Disc from Norfolk (PAS: NMS-B9A004)

(C) Portable Antiquities Scheme [CC Attribution 2.0]

Discovered in February 2012 in a field just outside of Norwich, the gold disc was legally declared as Treasure because it is over 300 years old and comprises more than 10% by weight of precious metal. The exact metal content is not provided, but at 20mm diameter and weighing in at 1.0g it is not a substantial object. Following the Treasure process, the disc was acquired by Norwich Castle Museum.

The delicate gold disc was originally recorded as an earring, but this identification is not definitive. The repousse decoration depicts an eye in its centre, lidded with a central pupil or iris, surrounded by eight figures primarily pointing towards it. Clockwise from the top these are: a lion (facing right), a phallus, a crab, another phallus, a snake, a scorpion, a single arrow, and a bow with an arrow notched and pulled back. The Eye, in this guise is the ‘all-suffering eye’ (Worrell and Pearce 2014, 419). In the Roman world the Eye is something that is feared. All was not lost as its malignant forces could be deflected or actively fought by other supernatural images. Movie goers might draw comparisons between this representation of Evil and the gloriously rendered Eye of Sauron in The Lord of the Rings movie franchise – and they would not be incorrect in doing so (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: The Eye of Sauron

Public Domain (from here)

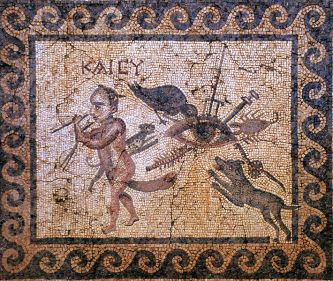

Bear with me here: like Sauron, the Classical Eye is always singular, always present, able to be distracted (Lord of the Rings plot point: when seeking Frodo and Sam in Mordor, the Eye of Sauron’s gaze shifts to the seemingly suicidal battle at the Black gate), and could be ultimately defeated by the actions of small men. The latter might seem most preposterous, but the most famous depiction of this ‘all-suffering eye’ scene is a second-century BC floor mosaic from a house in Antioch (Fig. 3). This example is attacked by (clockwise from the top) a trident, a sword, a scorpion, a snake, a small dog, a centipede(?), a macrophallic phallic dwarf/satyr playing the pipes, a cheetah, and a raven.

Figure 3: Mosaic depicting the ‘all-suffering Eye’

Public Domain (see here)

The first sentence of this piece suggests that the Norwich gold disc is magical; I appreciate that this is a bold statement, but the reasoning for this is that this iconography is wonderfully unusual and always bespoke in the specific ‘enemies’ it utilises to attack the eye. Exoticism, in this case of an image, can itself be regarded as something inherently powerful or which could be incorporated into an ancient magical ritual (see Wilburn 2012, ch.2). Additionally, gold certainly holds some form of amuletic function when used to depict phallic objects (see Johns 1982 and here), amulet cases, and lamellae. We haven’t yet covered my conceptual approach to what exactly magic IS or DOES in this blog (PhD Chapter 1 is in progress), but the use of the Evil Eye as an ethereal supernatural baddy is certainly interesting because it represents something to be feared and the mechanisms by which one might go about protecting oneself from it. i.e. it represents a sort of protective/amuletic instruction guide showing a cause-and-remedy situation.

The Evil Eye was very definitely a Roman import into Britain and, as an image, wasn’t hugely popular in the succeeding historical periods – largely, one assumes, because it did not fit as well into the Christian narrative of victory over evil coming ready-made with its own enemies personified into more nuanced concepts than the Evil Eye can deliver.

As an image, when the Evil Eye was depicted in Roman material culture it was most often being attacked. The only examples I am personally aware of that do so across the entire Roman Empire are phallic carvings and they do so in a very biological way (Fig.4). To be absolutely clear, these phallic carvings are ejaculating over an Eye. At least three examples of this scene are visible in carvings from Roman Britain – from forts at Maryport, Chesters, and a unstratified example from Lincolnshire. A recent find from Catterick might also show a phallus ejaculating towards an evil eye depicted on a different piece of stone (Parker and Ross 2016).

Figure 4: Relief carving foa phallus attacking the Evil Eye. Leptis Magna.

(C) Wikimedia Commons [CC By SA 3.0]

Looking at the ‘enemies’ of the Evil Eye one wonders if there are comparisons to be made with the Tauroctony narrative defining the Cult of Mithras. In the ‘killing of the bull‘ Mithras kneels on the back of the bull, Phrygian cap atop his head and cape billowing heroically in the wind, stabbing it in the throat with a knife. A small dog jumps up at the blood, which always has a snake to its left and a scorpion heading towards the bull’s testes to the left of that. A raven sits in the top left corner. This example has the torch bearers Cautes and Cautopates, and the sun and the moon deities at racing in the pediment but we can largely ignore these latter characters for the sake of this point.

Figure 5: Mithraic Tauroctony from Rome.

(C)Wikimedia Commons [CC 3.0]

At face value, lets compare the two images of the ‘all suffering eye’ with the Tauroctony: In the Antioch mosaic, the raven is in the same location, as is the dog leaping up towards the Eye and it has a sword stuck into its upper edge. The scorpion and the snake are also both present. In the Norfolk disc the scorpion and snake are in comparable positions to the Tauroctony but that is all that might match. Both leo (lion) and miles (soldier) are also levelled ranks within the Mithraic cult and a crouched lion is depicted in some examples of Tauroctony.

Does this mean anything? Well no, not that I would safely argue at this point, but I don’t think that the idea is just jumping at shadows. The images used in the battle against the Eye and in Mithraism both have celestial counterparts (indeed the Tauroctony scene largely depicts the Northern Hemisphere night sky if one takes Mithras as Orion), but individually have their own relevant (and wildly complex) iconographic histories. Snakes are associated with Asclepius, healing, and are sometime chthonic (with Medusa for example); phalli are the supernatural ‘lightning conductors’ of the Roman world; lions feature prominently in Roman art and are used as funerary furniture in Britain.

Suffice to say at this point that the little gold disc represents a hugely complicated historical narrative of protective imagery in the Roman world; there is certainly something more interesting going on here than just animals surrounding an Eye.

POST-SCRIPT UPDATE

Another one of these amazing things turned up in 2018 and was recorded by the PAS (see: KENT-DD7BC3).

In the January 2020 edition of the Roman finds Group Newsletter Lucerna I shared a note about an all-suffering Eye carving in the collection of Woburn Abbey in the context of a wider group of these images. It can be downloaded open-access HERE.

Bibliography

Johns, C. 1982. Sex or Symbol: Erotic Image of Greece and Rome.

Parker, A. and Ross, C. 2016. “A New Phallic Carving from Roman Catterick”, Britannia 47 [http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0068113X16000118]

Wilburn, A. T. 2012. Materia Magica: The Archaeology of Magic in Roman Egypt, Cyprus, and Spain. Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press.

Worrell, S. and Pearce, J. 2014. “II. Finds Reported under the Portable Antiquities Scheme”, Britannia 45, 397-429 .